What follows is a transcript of an email conversation that took place in 2023 between house music and electronic music legend Sunshine Jones and John Topley, discussing the Breaking Point album, being tall, astrology, ABBA, the meaning of the name TIERGARTEN and the grand tradition of synthpop.

Sunshine Jones: Who are you?

John Topley: My name is John Topley. I’m from the U.K. and I enjoy writing songs. By profession I’m a computer programmer.

SJ: How tall are you? What’s your astrological sign? How do you generally feel about astrology?

JT: I’m 6’ 1" tall. I’m an Aquarius. I don’t follow astrology, but I am very interested in astronomy. I love to go to talks at the local planetarium. The cosmos and our place in it is endlessly fascinating. I will never get bored or used to the idea that we’re seeing light from stars that no longer exist, because they’re so far away that it takes so long to reach us.

SJ: I think it’s great that you’re tall. Do you feel tall? Do you think being tall (over 6’) has had an influence in your music? That may seem glib, or silly, but consider that wild genius like Prince seems to come out of tiny little people (the purple one was only 5’ 2”) and so there’s potentially a drive for acceptance, to be more than overlooked which is natural in people who the mainstream may consider to be “short”. But I can’t really think of any “tall” musicians. There was “Tall Paul” but he wasn’t even 6’ was he?

I am 6’ 4” and I have taken a decidedly anti-fame perspective (think of me as an anti-hero, or part of the underground, such as it is) and I wondered if you think our altitude - which I would never ascribe to being an “advantage” per se - plays a role in our outsider nature, and musical intentions in general. Long set up for the question, but ultimately, have you ever considered that your height may have had some sort of influence on your art?

JT: I haven’t really viewed myself as being a tall person for a long time, but I suppose I must be. I would still look up to you though.

That’s an interesting theory. Almost like a creative form of a Napoleon complex. I have noted quite a few times how people who are successful in their chosen field often appear to be so because of great adversity (and often extreme poverty) in early life. Almost like their accomplishment is a result of a wilful reaction against their earlier circumstances.

I’m reading a biography of the Bee Gees at the moment. It’s written by Bob Stanley from Saint Etienne who is also a music journalist. Reading about their early lives, I had no idea how rough it was for them. They moved home regularly because their father couldn’t pay the rent (literally moonlight flits) and the young Barry, Maurice and Robin were often in trouble with the police for shoplifting and arson. It all could have turned out very differently.

SJ: As far as astrology goes, it’s silly, but it’s also mysterious and at times wildly uncanny. For example:

The Aquarius:

Aquarians are highly intellectual and creative, marked by independence, they don’t like to be instructed what to do.

While they can be social, they are not likely to participate in social interactions unless they truly want to.

Aquarians are ideas people, never suffering a drought of inspiration.

Famous Aquarians:

Harry Styles, Oprah Winfrey, Alecia Keys, Michael Jordan and Justin Timberlake (to name just a few).

I know you said that you don’t follow astrology, but surely the stars have some hold on your heart, if not your skeptical Aquarian mind?

JT: I think that horoscopes are cleverly written so that anyone might find a dose of uncanniness in there. The other day the first two lines of a new song, that’s lyrics and melody, just popped into my head from nowhere. I have no idea how that happens, but I’m grateful that it does.

SJ: What’s your background? Did you study music?

JT: Aside from music lessons at school I’ve never had any formal music education. I was hopeless at music at school. I remember scoring 4/20 in a test once when we had to write down how many beats a minim was worth, that sort of thing. The teacher we had was very old-school and was some kind of sadist. He used to throw board rubbers at people and torture us by making us sing ever higher whilst he played scales on the piano. I hated it. I learned nothing about music from him.

Then one day we got a new music teacher (there was a rumour that the old guy got sacked for assaulting a pupil) and it was as if a door had opened. He brought in these little Yamaha Portasound FM keyboards for each practice room and we were free to noodle around on them during break time.

I can remember one of the first songs I learned to play the melody of was ABBA’s Money, Money, Money. Dead easy to learn because the chorus is just the notes A, B, and C.

Following this I asked my parents for a home keyboard one Christmas and I ended up getting a better model each Christmas for three years in a row because I was really into it. I did the thing at first of sticking a little piece of masking tape on each white key with the note name written on it. As I got better at learning the notes I removed them all apart from the Cs. Then I removed those too.

I learned to play other people’s songs from books (sometimes with an accompanying audio cassette) and from there it seemed a logical but gradual progression to start writing my own music. I had to transcribe my music by hand using a pencil and manuscript books because a digital sequencer was impossibly expensive back then, even more so for a teenager at school. I still have most of those manuscript books, including the original music for what eventually became A Selfie With You and As If on this album.

More recently I’ve learned a little more music theory such as what modes are and what the tonic and dominant are by watching YouTube videos. However sometimes I watch those clips where they’re dissecting a classic Beatles’ song and they’re talking about how clever it is in terms of music theory and they’re so far up their own backsides it just kills all the joy of the song for me. Also, Paul McCartney never had any music theory, it was all talent and instinct. Writing music is quite intuitive for me as well. I can usually find something interesting to create.

SJ: Have you got a sort of a notebook of ideas, or scraps of theory, or lessons which you return to which eventually turn into songs? Is it that conscious for you? Or does it just kind of happen?

JT: I still have some old A4 notebooks from when I first started writing songs over thirty years ago. They contain chord changes and lyrical ideas. I also have about five or six manuscript books from that time with my handwritten sheet music. A lot of it is unfinished songs or even just drum patterns. I invented my own notation for those.

Nowadays I use my phone for capturing ideas because it’s usually nearby. It’s essential to capture an idea quickly with the minimum of friction because it only takes one distraction and then it’s gone forever. I have various notes of chord changes and fragments of lyrics. I have a long list of candidate song titles. I also have quite a few short video clips of little phrases I’m playing. Only this morning I sang two lines into my phone that popped into my head fully formed from nowhere, which will eventually become the start of a brand new song.

What tends to happen is that inspiration strikes, then I get the start of something or the kernel of an idea, but it’s very rare for me to see it through to completion there and then. An extreme example is What Would Marcus Do? whereby I wrote all the words and the verse music three decades after the rest of it. It’s very satisfying to finally finish a song in those circumstances, but I do worry that the later parts won’t be as good as the earlier parts.

It’s a conscious move when I’m out of ideas and choose to raid my old notes looking for inspiration. For example, I might be stuck on the music for a middle eight and then find an old chord change that works perfectly. I think that having an ideas bank like that you can make deposits and withdrawals against is an effective way to work, creatively.

SJ: It’s really interesting (and unique these days) that you have actually taken formal piano lessons in school. Do you think that training has influenced you? How do you think that lessons, even remedial ones in school, have helped to shape how you perceive and express music?

JT: I think I’ve given you the wrong impression. I’ve never had formal piano lessons. By which I mean learning scales, hand independence, grades 1 through 8 etc. I really wish that I had and from a young age. I would absolutely love to be a halfway decent piano player with all the correct technique.

SJ: Oh no, I didn’t misunderstand. I am suggesting that the tedious scales you played in school are more of a formal musical education than many musicians have had today. I was wondering if even having a root knowledge of chords and scales has been something that’s helped or potentially hindered your creativity?

I realise what a silly question that is. Anyone with a root musical knowledge would immediately insist that YES, it’s helped a lot. But my personal answer (and this isn’t my interview) is different. I wondered what your take on this was?

JT: It’s definitely helped. Not having to fumble around or consult a reference to find the next chord helps. It’s like being fluent in a language or even learning to drive. Once the movements are automatic the mind can operate at a higher level without getting bogged down by the mechanics. I don’t really pay much attention to scales though. I try not to get weighed down by what notes should fit what chords in terms of music theory. Undoubtedly a huge amount of the best music breaks the rules.

SJ: What about theory? Has that given you the keys to the kingdom? Or is it a hassle?

JT: That’s a very interesting question. It’s almost like wondering whether understanding how something works ruins it. Sometimes it does, but sometimes it can make you appreciate it even more.

I am very glad that I have a working understanding of how to read music (I can sight read, but not in real time) and how to write it. That was a consequence of how I learned to play the keyboard, learning along with books that had single stave notation of a song’s melody. It also became the only means I had of capturing my musical ideas back in the 1990s.

It has been of benefit to me to understand what a quaver, a crotchet or a mimim etc. is, although I only found out quite recently that those names are in fact British and not universal. That was a surprise.

I started by learning to play other people’s songs from books. Starting with Sloop John B, The House Of The Rising Sun, Flashdance et al then learning some Beatles’ songs, some 1980s hits and the music of the Bee Gees and Pet Shop Boys. I think that the sheet music book for Actually was the first proper three stave music book I ever owned and in fact I got it before I’d even heard the album! As an aside it’s very interesting to get the music for a song when you have no idea what it’s supposed to sound like.

Even to this day I will occasionally buy the music for something that interests me, regardless of age, artist or genre. I like to learn the trick to see how it’s done. It’s like having the source code for a computer programmer.

Just flicking through, I have Arthur’s Theme, Bright Eyes, Could It Be Magic, Daydream Believer, Harvest For The World, I Only Want To Be With You, Life On Mars?, Rock With You, Take Five, Wichita Lineman, the main theme from Star Wars...

Learning to play other people’s songs from books taught me a lot about chords. After learning a fair number of songs I found that I could remember how to play the most common chord types and I started to develop a sense of chord families and what goes well together. For example, Am to Dm. F to G. Bb to Ebm. D to G. Any sus4 chord resolving to the same major chord. That sort of thing. Later on you learn that it’s not the individual named chord changes that are important so much as the intervals between them.

There were really two revelations that I found formative and essential to my musical development. The first was the discovery of the maj7 chord which creates a very dreamlike feel. That was the gateway to the idea that you can just keep adding notes to a basic chord triad to make an ever bigger more interesting sound. Try playing a Cm chord with your left hand and at the same time a Bb chord with your right hand to see what I mean. That’s the beautiful sound of a minor 11th chord.

Take an Am chord and add an F and you have an Fmaj7 chord. Contactless started as an exercise in the idea that you can find smaller chords within larger chords. So the chorus is Fmaj7 then G7, but the verses are F, Am then B dim.

The second revelation was when I discovered how to relate note lengths to 16th notes and how to sequence them. I was learning to play Domino Dancing and the bassline has a lot of dotted 8th notes. My little Yamaha home keyboard had a primitive real time sequencer. I suddenly realised that I could slow the tempo right down to say 30 BPM and program the sequence precisely against a hi-hat playing 16th notes acting as a guide. So to program a dotted 8th note I just had to hold the key down for three hits of the hi-hat, then when it was done set the song’s tempo back to the correct value. In the absence of step recording that technique gave me very accurate machine-like sequencing in the late 1980s/early 1990s.

I enjoy the mathematics of music.

SJ: Do you spend much time playing other people’s music? Learning it, and studying it is one thing, but have you ever just sat down to a piano and united a party with your repertoire?

JT: I spend next to no time playing other people’s music nowadays. In reference to the discussion above, sometimes my only immediate interest in getting the sheet music will just be to look up a particular chord change. One example of this would be that wonderful unexpected chord change in the verse of Bowie’s Absolute Beginners. As I said, for me it’s about learning how it was done. Maybe one day I’ll get back to it and simply enjoy playing other people’s music for my own enjoyment again.

I did make a concerted attempt to learn Bach’s Prelude no. 1 in C major for the well-tempered Clavier earlier this year, but that was more of an intellectual exercise and because I’d bought the book How to Play the Piano: (Little Ways to Live a Big Life) which aims to teach anyone at all to play that one piece, out of curiosity. I was actually hampered from playing the piece all the way through by not owning a keyboard with enough keys!

I have never sat down at a piano and united a party. I do remember one time at one of our legendary sixth-form parties when I was 17 going up to an upright piano and playing the house piano riff from It’s Alright. However there were only a few of us in that room and we were all pretty drunk. If I’m in a restaurant or pub and there’s a pianist I always play close attention, I think it’s marvellous.

SJ: When was the last time you listened to anything by ABBA?

JT: I regularly hear ABBA’s hits on the radio. I think their best songs are phenomenal and of course there are a lot of them. Mamma Mia may well be my favourite. I once learned to play Super Trouper and I Know Him So Well (not ABBA, but written by Benny and Björn). The music is very interesting and satisfying.

SJ: Wow, the radio! Do you mean the actual bonafide terrestrial radio? What station do you listen to? When do you tune in?

JT: Yes, FM baby! In our house the radio is often on and it’s BBC Radio 2 (increasingly less so), BBC Radio 6 Music and Greatest Hits Radio (a commercial station). I also usually have the radio on in the car because it relaxes me a little bit.

As an aside, I think that FM is a lot better than DAB. In terms of the technology, not the content programming. Based on my own experience digital radio doesn’t really seem to work very well. FM seems a lot more resilient to signal degradation.

SJ: What are you trying to accomplish self-releasing an album in this day and age?

JT: That’s a great question. I made this album to express myself creatively and to offer some commentary on the modern world. I am releasing it to see if anyone out there is interested and wants to listen. In fact I think this is the day and age of the self-release, because technically it’s easier to do than it’s ever been.

The hard part is getting it in front of people so anyone can even have the opportunity to hear it in the first place. 100,000 songs are released every day. It’s hard not to feel rejected when you put so much effort into something and it doesn’t immediately set the world on fire, but it’s important to remember that people aren’t rejecting what they’ve never even heard.

SJ: 100,000 songs is a lot of songs. When you say “released” what exactly do you mean?

JT: Released for streaming on Spotify. Apparently that’s the number.

SJ: That’s an astonishing number. How does that make you feel about this release?

JT: It is an astonishing number isn’t it. It’s hard to imagine. This is where I have very mixed feelings about how technology has led to the democratisation of music making. On the plus side, it has enabled me to even make this album in the first place. When I first started writing songs thirty years ago, to realise this record would have been an impossible dream. The tech was financially out of reach and nowhere near as capable in the first place, I’d have needed professional studio time and of course there was no World Wide Web, which has provided me with the means to work with singers, musicians and producers all around the world and to distribute my music to anyone in the world who cares to listen. Incredible!

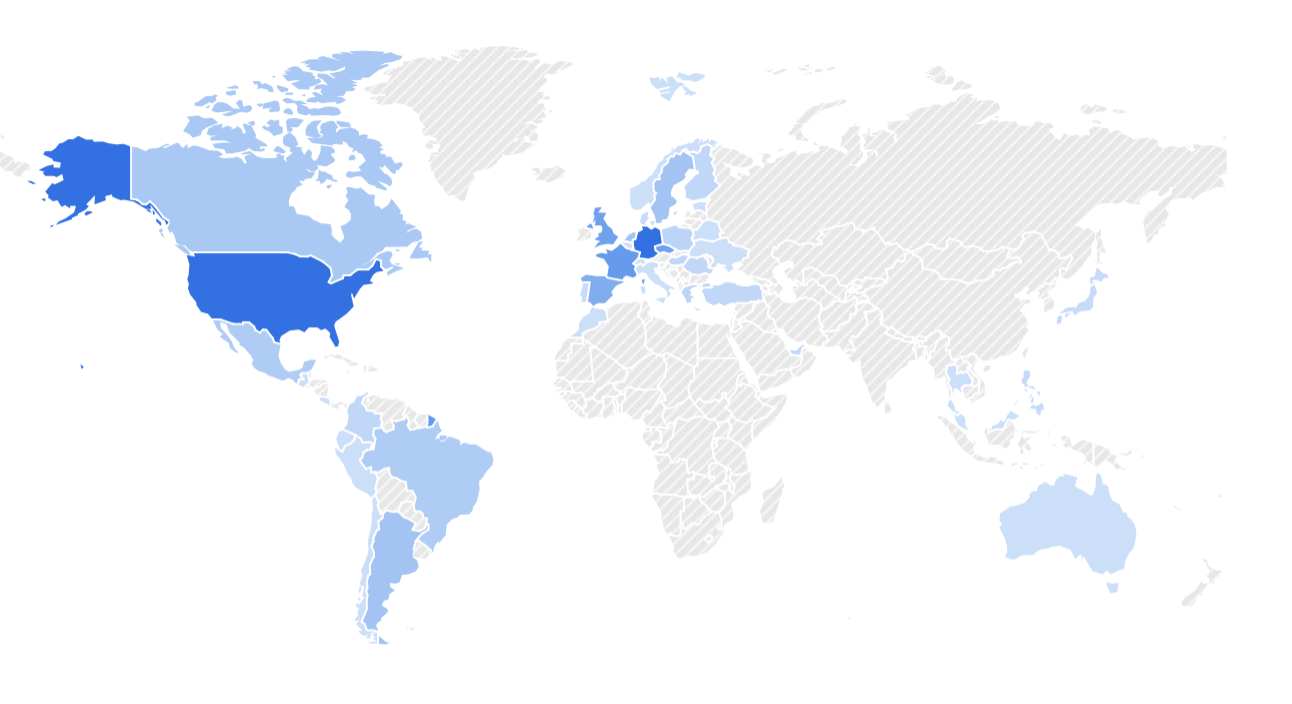

This image below shows the countries where someone has streamed TIERGARTEN’s first single As If on Spotify. It blows my mind to imagine someone from each of those countries listening to a song I started in my teenage bedroom...

The downside of the democratisation of music making is that because everyone’s at it, it is much, much, much harder to get noticed. Also, clearly music is massively devalued now. I mean, there are entire swathes of people, literally millions of people, who think all music should just be free at the point of access. It’s become more commoditised than it ever was. The more you make of a thing, the less each thing is worth. It’s simple supply and demand.

This devaluation has had a massive impact on the music industry. As well as how difficult the streaming royalties model makes it for an artist who isn’t a megastar to scrape together any sort of living, the money simply isn’t there to go into A&R and artist development like it used to be. I could weep when I think about all the recording studios that have been lost.

The Internet really is a double-edged sword.

SJ: I was watching the promotional clips for Yesterday’s Tomorrow and I really liked them. I really love that you’ve chosen to create such an interesting mosaic of images, the mirroring, and the positive color scheme. How much of people’s interest in clips, videos, and music in general do you think might be visual? Do you think that’s ironic?

JT: Thank you. The visual side is really all new to me. The promo clips for As If were a literal interpretation of the song’s lyrics. For Yesterday’s Tomorrow it was more difficult because it’s an instrumental. I was aiming to convey a sense of movement and a little excitement to match the music. Hence all the sped-up traffic footage. I was worried about it all being a bit cliched because we’ve all seen those types of clips before. I thought the microchip sequences worked really well.

I think that we live in a visual age more than ever before, because like it or not we live in the age of social media. For example, an awful lot of people nowadays listen to their music through YouTube, which I would say you and I think of as being for video clips and not primarily as a music distribution platform, but it is.

Then there’s the whole TikTok phenomenon. I really do think that in ten years’ time, or perhaps as soon as five years, mainstream pop music will consist of nothing but a chorus or hook within a thirty second song. A very small part of me is intrigued by the creative constraints of that, but on the whole I am appalled by what it says about our modern lack of attention.

The music video doesn’t really exist anymore. Which is quite something when you consider what a big deal it used to be. I think it’s hilarious that "Music Television" (MTV) doesn’t show music videos any more. People like Damian Keyes, who advise budding musicians on how to break through in the music industry by building a fanbase through social media, actually say not to bother making a music video now. It’s all about 30, 20, 15 seconds long clips. Everything used to be shot in landscape because that’s what the cinema used on a big wide screen. Now everything is portrait.

We live in an age where the visuals and the music are inseparable. The kids are sharing a song with their friends by messaging them a link to a clip on TikTok. The music is actually in support of the visuals, not the other way around.

One thing that gave me heart recently was the re-emergence of the cassette. Not the actual cassette because it’s a terrible-sounding format, but I read that some youngsters who were born long after the format died like it because it forces them to listen all the way through. There’s no easy way to skip ahead. I found that very interesting.

SJ: For someone so new at this, you’re off to a fantastic start. Do you have a Tik Tok account?

JT: Thanks! I do have a TikTok account, see https://www.tiktok.com/@tiergartenmusic As of this writing none of my little clips have broken through the 300 views barrier, which is apparently because I’m not using any wacky gimmicks, captions and emoji. In other words they’re probably dead boring.

I’m not very good at social media. Or rather I struggle with the imperative to be creating and posting content regularly. I get it - imagine we’re having a great conversation and then I disappear with no warning for three months. You might be a wary about engaging with me next time.

Building a significant social media following is really a full-time job. I already have one of those, so I’d rather spend most of my limited free time on the aspects I enjoy the most i.e. writing and producing the songs. That said, I have been enjoying making the promo clips.

SJ: Why is your band name TIERGARTEN? What’s it mean?

JT: It doesn’t mean anything per se. Well, it’s the German word for "zoo" and it’s a district with a big park and a zoo in Berlin. I went to Berlin for a conference once, but I never made it to the Tiergarten. I came across the word in a novel I was reading a few months ago and I liked that it was a mysterious-sounding single German word like Kraftwerk. I also like how it looks written down. I needed a name for this project so why not?

SJ: I love that it’s the German word for Zoo. Or, rather, the name of a zoo in Berlin. That’s actually fantastic. When I hear it, I think, naturally as an English speaker, that it means something like a tear garden, or a garden of tears. Seems like you’re threatening to bust out a vest of feathers, and do spastic dance moves, and really really mean it. But how fantastic that it’s the name of a zoo. Did you mean for it all to be a bit ironic, or maybe even rolling out a bit of double entendre? Your music is not entirely flossy, but it is relentless and even with your more challenging subjects, motivated, and optimistic in its notation and over all feeling (even the moody ones) but I wondered if that vinegar in the honey (or is it sugar in the salt?) might have a representational purpose for you? I mean, I get that it’s just a name, but it’s your name, and you chose it, and stood up when called. So is that where you were coming from? Laughing that life’s tear garden isn’t so horrible after all?

JT: Prompted by this I actually looked the word up. The literal translation is "animal garden". Rather than tears I was coming at it from being like the tiers of a wedding cake i.e. a layered garden, but we now know that’s wrong.

I like the idea of a garden of tears, that’s a fascinating interpretation. I didn’t mean for it to be ironic or have any deeper meaning at all. As I said, I just came across the word in a book and liked it and wrote it down. I do enjoy that people might try to read other things into it though.

It’s an abstract name, but I’ve always liked music with the contrasting qualities you describe. One of the reasons I love the Pet Shop Boys is that their best work manages to pull off uptempo happy music with melancholic words.

SJ: Right T, I, E, R as in a 3-tier keyboard stand. I get it. But hearing it, or saying it, I see images of a garden of tears. I think the association is unavoidable, and so I wanted to get this question put right to bed.

SJ: This is not a club record, or even really a “dance” record. It is pop music without the gloss or the dumb of modern “radio” music. What would you call it?

JT: I would call it synth-pop in the grand tradition. I hesitate to use the phrase, but really it’s also intelligent pop music. In the sense that it has something to say. With the exception of the general sentiment of Heyday, none of the songs on this album are about me or anyone I know. Most contemporary pop music seems to be autobiographical and I find that really boring. I think there are much more interesting subjects to write about than oneself.

SJ: I am thrilled with the idea of a “grand tradition” of synth pop. I actually dearly love synth pop. I am a huge fan of musicians, composers, and producers from the late 70’s and early 80’s. I think that was a very special time when many ideas clashed together like the wrong paint on a bank, and wonderful things happened.

Can you tell me a little more about who you admire from the golden age of our grand tradition?

JT: All of the obvious ones. The Pet Shop Boys shouldn’t come as a surprise. They’re my favourite group and have been since they started. Kraftwerk. The Human League, both before and after the big split. Soft Cell. Depeche Mode, particularly early on. OMD. New Order. Electronic. Yazoo. Erasure had some cracking tunes. Giorgio Moroder. Some of Sparks. I think that Ultravox are often overlooked. The tempo and bassline of What Would Marcus Do? were completely inspired by Dancing With Tears In My Eyes.

Pop Music by M is a wonderful synth-pop record. Im Nin Alu by Ofra Haza blew my mind. I know that you love Japan and I need to dig into them.

SJ: Fantastic examples. Thank you.

Do you think there’s an audience for electronic music off of the dance floor?

JT: I think so. Obviously genres and trends come and go. There was a time in the 1980s when synth-pop was the dominant form of pop music, co-inciding with the emergence of affordable synthesisers in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Just as rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s was driven by the widespread availability and adoption of the electric guitar. People eventually grew tired of that 1980s synthesiser heavy sound and something else took its place.

I don’t really know anything about contemporary dance music. I used to live for the nightclub, but I lost touch in the mid-1990s. When I was growing up it was really quite polarising in the sense that you were either into rock music, so-called real music played on real instruments, or you liked electronic music/dance music. There wasn’t much middle ground, but that seemed to change with the blurring of indie and dance music in the late 1980s and early 90s with groups like the Happy Mondays that used guitars, synths and samplers. Of course New Order had been doing that all along, but by the time of Madchester it was everywhere.

Today it seems that dance music or EDM as they call it "won" and became the ascendent form of popular music. You just hear it everywhere, don’t you? That kind of cheesy low-effort sound with heavily processed vocals that represents a sort of reality television celebrity party lifestyle. It also seems to have fragmented into countless sub-genres. Just looking on Wikipedia...who the hell knows what "Fidget House" or "Martial Industrial" are?

SJ: As an artist who made their way through the last 30 years of 12” singles, DJ culture, warehouse parties, and all the rest of that I absolutely love that I am talking with an electronic musician who didn’t actually pay any attention to any of that. I think that’s marvelous.

JT: What happened is that my best friend at the time moved away, I stopped going to nightclubs therefore I was no longer immersed in that culture. I was living in a provincial city in the east of England, so there wasn’t really much of a club scene. The dance music records I was getting exposed to on the radio...that Pete Tong was playing on his Friday night Radio 1 show before going out time ceased to be interesting to me. Rave music had happened, everything got crazy and sped up into drum and bass and jungle, then trance hit. I liked the euphoria of it at first, but to my ears it very quickly became samey and boring. Obviously there’s also great music outside the mainstream being made if you know where to find it, but I’m relating my experiences of that time. Finding it meant physically finding it. I wasn’t doing that.

I think if I’d been living in a major city then it could all have been very different.

Something that also happened back then is that remixes started to become completely new pieces of music. I increasingly noticed this when I was buying Pet Shop Boys’ singles. From about 1994 the remixes really bore no resemblance to the original track other than perhaps a little vocal sample.

Something I always liked about the great 12" mixes from the 1980s was that they’d showcase the different elements of the song that you wouldn’t necessarily be able to hear in the 7" mix because there was too much else going on. So there might be a breakdown and you’d get to hear how brilliant the drum programming was or the isolated bassline. I absolutely love that. That’s something I try to do with my own extended mixes, although it’s a very old-fashioned approach. I’m making them to be listened to, not for the nightclub dance floor. You can dance to them in your living room or bedroom if you like.

SJ: Far out, so you feel that NOT living in London or Manchester has been a defining aspect in your relationship to music, and in your own creativity? I wonder how you feel about music in solitude vs music as a collaborative or performative experience. I mean, let’s say this goes smash hits on you, and you have to gather yourself up and get in front of folks in cities. Are you up for that?

JT: Who amongst us can tell how the unchosen life turned out? Undoubtedly out there in the multiverse somewhere I moved to London aged 18, got fully immersed in the club scene, met my lifelong musical partner and spent the past 30 years releasing records that are well-regarded in certain circles.

I have next to zero experience of music as a performative experience. The best friend I mentioned who moved away a long time ago, we did some brief musical things together, but it was just messing around with a keyboard. It was hardly riffing off another musician. We did nearly come to blows once over a bassline.

I am open to musical collaboration, but I am a control freak so it might be challenging for the other person or people.

I don’t see how getting up in front of folks in cities could possibly work, because TIERGARTEN is a project for showcasing my songs. There is no "act" that can get up on stage and perform.

SJ: So then are you drawing your influence and inspiration from the past? Or are you riveted to some Spotify playlist where jams like this are happening? I’m inclined to agree with you that music is music, and genre and style are kind of marketing button-holes for pushing the algorithm, and I tend to avoid those suggestion selling weirdos, and side bars. But it’s amazing to me to think that there is anyone out in the wild without human contact, without collective experiences, all asynchronous, and disassembled gaining momentum, getting the same hair cuts, and holding up banners for bands by way of the YouTube experience. Of course there are the stars of these platforms, but they are the novelty artists, the jokes, the nudists, and antagonists who seem bent on getting millions and billions of followers and likes that don’t mind the detractors or the hecklers. Like a mass radio response team…hardly an arena for collecting listeners, and allies, or any sort of a cohort, right?

So if you’re not coming up via a miniature replicant genre from somewhere new, then where will you come up? Is there a space to fit through? And if you fit through, where will you be? Where will you go from there?

JT: I’m not riveted to some Spotify playlist, but without question I owe a debt of gratitude to the artists that I cited above, some of whom are still around, but none of whom emerged in recent years. I would say that I am often addressing contemporary issues e.g. A Selfie With You, Contactless, As If, but the music and songwriting values are inspired by music from the past.

Something I struggle with and frequently question is where the dividing line between inspiration and pastiche lies. It’s hard to know. For example, I had the urge to put some orchestral hits on A Selfie With You, but resisted and instead tried to make a new sound that performed the same function. At the same time, there are some TR-808 sounds on the album that are just as well-worn. I don’t really know when something is a use of a classic instrument and when it’s just a hackneyed piece of laziness. Maybe it’s all about the context and how you’re using it?

With one or two specific exceptions, I am not intentionally setting out to make music that sounds like it comes from my youth, but I did write a lot of songs back then and that is the music I love the most. I don’t think I would know how to make a contemporary-sounding track. Technically I could listen to one and analyse the elements and try to replicate that sound, but I don’t particularly like it. Especially the way vocals are so heavily processed nowadays.

I do like some modern stuff. I thought One Kiss by Calvin Harris and Dua Lipa was a fantastic record. If I hear something on the radio that I like then I will buy it. I’m not a purist. A friend recommended the German duo Ströme to me on Bandcamp. I’m glad they did because it’s wonderful electronic music made with a Moog modular. Check them out.

As I think I related to you previously, one of the main reasons for relaunching my musical output as this project was to put it out there and to see if there’s any audience for it. It feels to me that people who like the music of the Pet Shop Boys and synth pop in general ought to enjoy at least some of my music. I know that you detest comparisons to other artists, but I am not claiming to have invented anything original. I love that style of music, I think it still has legs and that there are still interesting things to say and explore within that creative framework.

All that said some of the unfinished songs on my backlog feature a lot of acoustic piano with some big jazz chords, so there may be a partial move away from synth-pop in the future. I think it’s important to be open to any genre and to use whatever works best for the song. I’d really like to try to make a reggae song…

SJ: I love the idea of a big jazz chord. That’s exciting! If I were sitting beside you right now I’d probably insist that you play a few for me.

Most musical movements seem to come from the street, and then rise into culture, and by the time they get to the radio they’re hacked to shreds and haven’t got much meaning or value apart from the art of “pop”. Are you a part of a movement? Or are you reaching back and nodding to the past?

Who is the audience for this record?

JT: I am not knowingly part of a movement. I don’t feel like I know much about movements nowadays. I guess I am tacitly reaching back and nodding to the past in terms of trying to write the kinds of songs that I liked to listen to from the 1980s and 1990s. Actually even from the 1960s and 1970s.

I still think the idea of having three and a half minutes for a pop song that has things to say about something interesting rather than being a diary of a broken relationship or whatever is really creatively worthwhile. Like Waterloo Sunset being a character study of two lovers meeting at Waterloo railway station. Or Rent being about the power dynamic in a couple where one of them is a kept man or woman. We seem to have lost that art nowadays, at least I’m not generally hearing it in new songs on the radio when I’m washing the dishes.

I think the audience for this record is anyone who still appreciates that sort of songwriting.

SJ: How did you make this album? Why did you do it that way?

JT: With great difficulty! The album took about two and a half years elapsed time to make. I worked on it in my spare time, grabbing an hour here and there. I tried to do something every weekday before starting work. I think if you’re serious about your own creativity then practising it daily even if you only have twenty minutes is a good habit to get in to.

I wrote Contactless in April 2020 and then decided to start the album proper when I wrote Yesterday’s Tomorrow that December. The music for A Selfie With You, As If and the intro and chorus of What Would Marcus Do? is thirty years old.

Most of the recording was done in 2021. I wouldn’t say it’s my lockdown album, but I think what the world went through with Covid plays in to the sentiment of being pushed to breaking point. I certainly felt I was at breaking point at times whilst making it, wondering if it was ever going to be finished. In fact I called the album Breaking Point because some of the songs are character studies of people on the edge of losing it.

Apart from a limited use of plugins, all of the electronic music is from physical synthesisers and drum machines, rather than virtual instruments. I thought it was important to work that way. I don’t find using a laptop to create music to be inspirational, I prefer to use the laptop as a digital tape recorder, effects machine and virtual mixing desk only. I don’t write songs using it.

Something that ended up happening during this album was using a song as a means of trying out a new synth. What Would Marcus Do? is the sound of me trying out the Roland JP-08. For Solving For Love it was the Roland JX-03. There’s also a Korg Volca Keys and a Roland SE-02 on the record, but I no longer own either of those instruments.

Most of the writing was done using the Synthstrom Deluge. I used it to create the original demos, although if I had an instrument with a physical keyboard in front of me I’d also use that to work out chords and melodies. I’d typically end up using my demo projects on the Deluge to sequence the other instruments such as the Roland SH-101 or Elektron Digitone whilst recording properly. The instruments were all recorded one at a time on my living room table, where we eat dinner.

The album was mixed and mastered by Doctor Mix, an online mixing, mastering and production service.

I had to make the album this way out of necessity. I don’t have a dedicated studio space with professional monitoring. I did the best I could within my circumstances.

SJ: I want to comment here, more than following up. I think that the hard work you put into this album really shows. The music is just lovely. It’s a real step forward for you both as a songwriter as well as a producer. I love that you got help, held conversations over a long period of time, got well out of your comfort zone, and actually finished the record simply because you personally needed to as an artist. That, to me, says it all, and brings such an honesty to this work that I stand delighted, and inspired.

JT: Thank you. That means a great deal to me.

SJ: Who are the singers? Why did you choose them?

JT: They are session singers that I paid to sing my songs for me. I’m not going to name them because one of them wishes to remain anonymous. I browsed SoundBetter and chose people who had had voices I liked and good reviews. It’s almost impossible to get any sense of how someone else singing your song will sound until you hear it. For my demos I used the Emvoice One vocal synthesis plugin. Drenched in reverb that also provides the angelic voices you can hear in the middle section of Solving For Love.

SJ: There is a stark contrast for me, listening, to songs like The Face In The Photograph or Waves and A Selfie With You. Where I am drawn deeply into the instrumentals, I am repelled by the vocals. Did you do this on purpose? What are you trying to say with the vocals as a writer or a producer beyond the lyrics you’ve written?

Contactless is another controversial song for me. I think it’s very important. And yet the vocals are so hard to listen to, and don’t seem to go with the music at all. Is this a part of the production/composition decision of the song’s subject? Considering that you got the singer over the internet, and never met them, are you making a larger statement with these choices?

JT: No. I find the idea that I deliberately chose vocals that are repellent to you as some kind of artistic choice or statement to be pretty insulting. Of course I didn’t do that on purpose. If I had found the vocals to be as hard to listen to as you clearly find them then I never would have used them.

SJ: I want to say it here, without intending any disrespect to the talent of your singers, but I don’t know if I feel that TIERGARTEN have found their singer yet. There’s something I feel strongly while listening to this record, and it’s that the voice is not that of a person involved with what you’re talking about. I almost hate to bring this up in a more formal setting, but personally I just ache for this voice.

You’re saying that the disconnect that I perceive is not ironic, or intentional so I have to ask you why you didn’t grab the microphone and sing these words yourself? Why didn’t you haunt the local record shop, or audition hundreds of people until you found your artistic soulmate?

I wonder if anyone does that?

So to set the incongruity aside, tell me a little about your favorite singers? Are there some you love?

JT: I didn’t just grab the microphone and sing these words for myself because I am not a singer and am not a performer. Of course you could say that everyone is a singer, but what I mean is that I don’t immediately have the ability to sing confidently, unselfconsciously and even in tune. I might be able to get there one day with lessons if I were so inclined, but the imperative was to complete the album.

The idea of auditioning hundreds of local singers honestly never occurred to me. I wouldn’t know where to start.

There are also practical issues around vocal recording setups, equipment and knowing how to use it. The logical approach seemed to be to hire some professionals to help me realise these songs, rather than relying on chance.

Not surprisingly, I love Neil Tennant’s voice. It’s so distinctive; particularly his spoken voice on the records. Sometimes I think I like Bernard Sumner’s voice even more. He reluctantly took on the role of singer and has made it his own. What I like about his voice is the quality that was once memorably described as singing the words as if they’d only just occurred to him.

I adore Tracey Thorn’s voice. I like the hectoring, rather brutal quality of Phil Oakey’s voice. Dusty Springfield and Scott Walker were amazing and so distinctive. I’m also partial to the big-lunged, powerful sound of people like Jocelyn Brown.

SJ: Have you ever read The Manual by The KLF?

For the UK this may be a trite or absurd reference, but as a North American this is unknown literature for the most part, and there’s a lot of fascinating (and hilarious) information in it about how to build a band, record a record, and (in theory) find yourself on Top of the Pops.

The KLF book also has a lot of very slack references to how those two came together, and rounded up people to do things.

I suppose the stars will send you "your singer’ when they see fit to do so.

JT: Yes, I actually read The Manual on your recommendation! It’s something I’d been meaning to track down and read for years. It’s a fun little book, but it hasn’t necessarily aged that well. There’s a great gag in it I can’t quite remember about working with a bass player. One thing it recommends that I quite often find myself doing naturally anyway is to have the song title in the first line of the chorus.

Sadly Top of the Pops hasn’t been on for 17 years and I miss The KLF. I think people of our generation perhaps look on them fondly as my parents’ generation looked fondly on The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown. Everything’s a bit boring nowadays isn’t it? No-one’s setting fire to their own head or firing a machine gun at music industry executives during an awards show.

SJ: What have you got against Kraftwerk?

JT: The Tragedy Of Kraftwerk is a provocative title isn’t it. Something I picked up from the Pet Shop Boys was the importance of having interesting song titles. I have nothing against Kraftwerk. Like probably everybody who has ever made electronic music I love them. Their music, their image and their mystique.

I read Karl Bartos’s autobiography and let’s be honest, I should imagine like everyone else who picked up that book I was most intrigued to read about what it was like to be a member of Kraftwerk during that period when they made their classic albums. They had such an incredible run of groundbreaking records: Autobahn, Radio-Activity, Trans-Europe Express, The Man-Machine, Computer World and then they more or less disappeared. As Bartos puts it in his book, they missed the 1980s just as everyone else adopted the sound they pioneered. That is the tragedy of Kraftwerk. The lyrics directly address the history, which is Ralf and Florian’s obsession with cycling and spending five years mastering their newly acquired Synclavier.

The song came very easily. I wanted to see if I could make a track that sounded like Kraftwerk.